In Conversation: Sarah Vowell

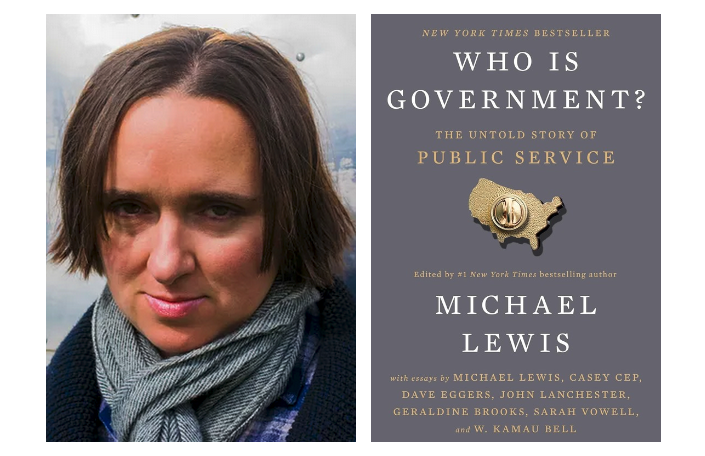

The bestselling author of seven nonfiction books on American history and culture talks with Andrew Richard Albanese about her recent contribution to Michael Lewis's 'Who Is Government' and why the country may soon learn a hard lesson about the importance of government workers.

In his 2018 book The Fifth Risk: Undoing Democracy bestselling author Michael Lewis explored how the first Trump Administration plunged our government into chaos, talking with many of the public servants who kept our government running under enormous stress. And last month, Lewis returned with a new book of essays Who Is Government? The Untold Story of Public Service, featuring contributions from seven bestselling authors (Casey Cep, Dave Eggers, John Lanchester, Geraldine Brooks, Sarah Vowell, and W. Kamau Bell) profiling civil servants who are doing important work.

First published as a series in the Washington Post, the essays are especially timely given the Trump administrations indiscriminate firings of civil servants—including at the Institute of Museum and Library Services, the agency that oversees the distribution of virtually all federal funding for libraries.

I recently had a chance to talk with historian and journalist (and actor) Sarah Vowell, the New York Times bestselling author of seven nonfiction books on American history and culture, whose beautifully written contribution to Who Is Government explores the National Archives through the work of Chief Innovation Officer Pamela Wright. We spoke about the important work of civil servants, how we’ve arrived at a place where government workers have become the object of scorn to one political party, and the importance of telling—and confronting—our history truthfully.

Tell us a little about what drew to you write about Pamela Wright and the National Archives? You’re a historian, so I’m sure that was part of it, but anything else?

I actually wasn't looking to write about the National Archives, per se. I am from Montana, so I wanted to write about a westerner and I found Pamela Wright, who was the Chief Innovation Officer for the National Archives, and who grew up on a ranch in Conrad, Montana. I came at this really just looking for just a Westerner, partly because, like many people across the country, I had once thought Washington D.C. was kind of a dirty word. But then, when I was young, I interned at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art, and that completely changed my idea about Washington D.C., because I got there and everyone was from the rest of the country, like me.

Pamela Wright’s mission was to digitize the National Archives, and I could see pretty much within the first five minutes of talking with her how being from a ranch in Montana affected the way she approached her job. Because the Archive’s mission for the last 50 years has been not only to preserve our federal records but to share them with the public. There are about 13 billion federal records in the National Archive and so far, Pamela and her team and her team of volunteers have digitized about 300 million of them. It’s important work, because America is a big country. Pamela Wright’s hometown in Montana is a 32-hour drive from the National Archives, I calculated. So, there was something really democratic about her mission, because these records belong to the American people and making them widely available online is just fair.

It must have been quite an experience to explore the National Archives with these career civil servants walking you around and showing you all this cool stuff.

Yes, I visited the main Archive building near the mall in Washington, D.C., where they have the rotunda with the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence on display. And I also went to a storage facility in suburban Maryland, which is much less august. It looks more like a community college in Indiana.

At the main archive in Washington D.C., the one with all the marble that Franklin Roosevelt put so much money into, I spent time in what they call the vault, and it's exactly what it sounds like. It’s not some magisterial place from like from National Treasure or something. It feels more like being World War II submarine. It’s gray, with metal shelves, and no windows. It’s a very government-funded aesthetic. And It’s where the national treasures are kept, like the Louisiana Purchase, which I saw, and, you know, just boxes and boxes of records. And it's presided over by a man named Trevor Plante, who actually inspired a character in one of Brad Melzer’s novels.

So, Pamela Wright and I spent some time with Trevor in the vault, because to write the profile of Pam, I figured I would tell her story through some of these documents. That's why we looked at the Louisiana Purchase—Conrad, Montana, where she's from, is just east of the Continental Divide and the northwestern edge of the Louisiana territory. We also looked at the Homestead Act, signed by Abraham Lincoln, because that's how her Norwegian American grandpa ended up in Montana. And we looked at the Higher Education Act of 1965, because without that Pam wouldn't have been standing there as an employee of the National Archives.

In the essay you write that it was like science fiction seeing Pamela standing in front of the Higher Education Act. Why was that so moving?

Because it’s how she ended up on this path. When she was a student at the University of Montana in Missoula, she had a job in the federal work study program, which was part of Higher Education Act of 1965. The program provided students some funding for their education as well as work experience. And she happened to get a work study job at the Mansfield Library at the University of Montana, in their archives. Her first job in the archives was transcribing oral histories of smoke jumpers in the West. And that was not only how she got her first taste of archival work, but it was also her first taste of what a middle-class, professional life would be like. And I had almost the exact same experience, down I-90 at Montana State, doing work study in the photo archives of the Museum of the Rockies. For a lot of working-class students, these work study jobs just gave us a sense of what a professional life would be like.

And you know, these documents in the archives, they really tell our stories. There are these direct connections in there—Pam actually sent me the actual Homestead Act land entry case file of her grandpa's homestead. But there are all these big laws, too. I mean, over maybe six weeks in 1862, Abraham Lincoln signed the Homestead Act, the Pacific Railroad Act, and the Land Grant colleges act. The college I went to was one of those colleges. In exploring the archives you really get a sense of how government used to have grand ideas about the future. Pamela Wright and I are both part of that legacy.

I think that’s one of the things that makes your essay so powerful, that you make these documents in the archives so relatable to all of us in our own lives. You even found some ties to your own personal history in there, didn't you?

Yeah, one of the things Trevor Plante sprung on us when we were in his lair—and I didn't ask to see this—was the Treaty of New Echota. That treaty, which was signed by a few unauthorized members of the Cherokee tribe, is what gave the United States government the legal cover to put the Cherokee tribe on the Trail of Tears. And that's how both of my parents’ ancestors were forced to walk at gunpoint to Oklahoma. Seeing that was really emotional for me. I actually burst into tears, because, for one thing, that document was a death warrant for about 4,000 people. But also, seeing such tangible connection to history reminds us that these signatures on these pieces of paper really affected people's lives.

In the essay, you write that researchers can pretty much find support for whatever they are looking for in the archives—if you’re looking to see the United States as a white supremacist ordeal, it’s there. If you're looking for evidence of progress, that’s there too. I think that’s an important observation in light of what’s happening with book bans around the country, and with some of the efforts of current administration. Can you talk about the importance of capturing, preserving, and engaging with our history—warts and all?

Well, we all love to have our assumptions confirmed. And if you have a point of view, you can certainly have it confirmed in the archives. For example, another things I say is that if you think government is too big, the 13 billion records in the archive will probably confirm that. But the truth is, once you dig in, the story is just so murky. I mean, I spent a little bit of time talking about Richard Nixon, who probably had more effect on the National Archives than any other president, just because a lot of laws were passed after Watergate involving federal records, presidential records, and holding on to those records so presidents and their administrations could be held accountable. The Watergate tapes are in the archives. But so too is the Clean Air Act that Nixon signed, which saved tens of thousands of lives, and the Blue Lake bill, which returned thousands of acres to the Taos Pueblo in New Mexico. So, Nixon, like the country, was not only one thing. And I don't really know what to do with any of that—it’s just the truth.

You mentioned that you were an intern at the Smithsonian, and I wanted to ask you about the Smithsonian, because President Trump last month signed an executive order tasking the Vice President with ridding that institution of what he called “improper ideology.” It seems Trump only wants stuff that supports his view of American greatness. But isn’t the story of American Greatness the story of how we evolve, the progress we make, and the fights that we have undertaken?

You know, that's so true. I didn't write about this in the piece, but in randomly poking around that Archives I found this report by Cyrus Vance Sr., who was an attorney in the Johnson administration at the time. LBJ, had sent him to Detroit after the Detroit riots to find out what was happening on the ground, and what the government needed to do better. And in this report, here’s this government lawyer sharing his point of view that if these protests are going to keep happening, one thing the government needs to do is to make sure there are enough attorneys on the ground for when protesters get arrested, because they are entitled to due process and they have constitutional rights. And that was just so moving, because the Constitution was just so ingrained in his way of thinking that he came back from the Detroit riots thinking that protesters need attorneys, because that's their right as Americans.

In his epilogue to Who Is Government, Michael Lewis writes about how popular the series was when it first ran in the Washington Post, and questions why publishers and newspapers don't run more stories about what civil servants actually do. Lewis acknowledges that the PR wing of the federal government doesn't really get to play offense. But it feels like that has allowed Elon Musk to fill the void by casting civil servants as fraudsters ripping off taxpayers. Now, I can understand being wary of government. But it seems to me that the anti-government animus today has been weaponized and refocused on government workers—and that feels a little dangerous. With so many federal civil servants now being summarily dismissed and agencies wound down, what’s your take?

Yeah, so there's a lot to unpack there—that’s a very loaded question! I mean, I think the anti-government stuff ramped up with President Reagan. He’s the one who said the nine most terrifying words in the English language are “I'm from the government, and I'm here to help.” But, mostly, help is what the government does. Some of this also comes from our founders, of course, who were tax protesters so concerned about the abuse of power that they designed a government with all these checks and balances. And you know, a lot of people just don't want to pay taxes, so there's that, too.

But as you alluded to, I definitely think the federal government itself has not been great at telling their story, of explaining to the American people who these civil servants really are and how they're spending our money. And I think all of us on this project, encountered some resistance to doing our stories. That was partly because we were originally reporting this for The Washington Post, and you say Washington Post in Washington D.C., and everybody's on edge. But I had to be followed around by a press officer the entire time I was on the ground at the National Archives. For most of us, the press office just wanted us to write about the political appointee running their agency. They really weren't keen on us going into the middle of these agencies and just talking about what their people do.

And another part of it is that these civil servants tend to be pretty humble. One of the people that Michael Lewis wrote about in The Fifth Risk was a guy who worked for the Coast Guard who figured out how to find people who were lost at sea. Turns out Americans have a problem of going overboard. And this one guy in the Coast Guard, Arthur Allen, did the math and computer models for years and years and figured out how to rescue people. But he just wasn't a self-promoter. In fact, he was amazed that someone wanted to tell his story at all. And it was the same thing for me with Pamela Wright. She was so modest. Like a good leader, she wanted her team to have all the credit. And I respect that. But I also think that is one reason why the country is in the dark about what all these civil servants really do.

I’m sorry to say that I think we're about to get real hard education over the next few months and years. Because the people being fired now are the people who take on the problems that may not be profitable to solve. That's really what the government does.

In the library world, so much advocacy is based on telling the stories of what libraries do in their community. But, like you experienced, it can sometimes be hard to get librarians to tell their stories because they're just so into actually doing the work for their communities. But if we aren't telling these stories, that's an opening for DOGE and the "Deep State" crowd to step into the breach, right?

Yeah, there's a real idealism among so many civil servants, and it goes against the grain of most elected officials who, as a matter of course, have to spend their entire careers tooting their own horns. For politicians, it’s a lot of talk and fewer solutions, whereas with these career civil servants it's pretty much the opposite. It’s about doing. It's only doing, and never bragging.

And look, I'm all for the government being more efficient and effective. There's actually a government agency whose job it is to figure that out. They're called the Government Accountability Office. And I don't even have a problem with the term ‘Deep State.” Call it whatever you want. But whatever you call them, civil servants are a bulwark against what we, the voters, do to our country. Because what voters do is we pick someone to be president, who appoints people from his party to implement their fussy ideas. And then four years later, we're so fickle, we choose the exact opposite for the next president. But its these dedicated civil servants who keep the ship of state running.

I think we're all, as a country, about to learn more about how that process works, or maybe used to work. It seems to me that a lot of these programs and agencies and people we’re letting go are trying to solve the problems of the future. So where will this leave us? What diseases won't get cured? What problems won't get solved?

You wrote your essay before the Trump Administration got into office. Have you heard from Pamela since?

Pamela retired in December, before the new administration came on. You can read into that however you want. And I think the archives is in flux because the president fired the previous Archivist of the United States, which is his right. That position is filled by a political appointee. Right now, the acting Archivist of the United States is Marco Rubio. And I’m guessing he’s probably focused on a few other things.